INK. Groupshow

2 May to 7 June 2025 ⟶ Galerie

Exhibition view Georg Nothelfer Gallery. Photo: Katrin Rother

Exhibition view Georg Nothelfer Gallery. Photo: Katrin Rother

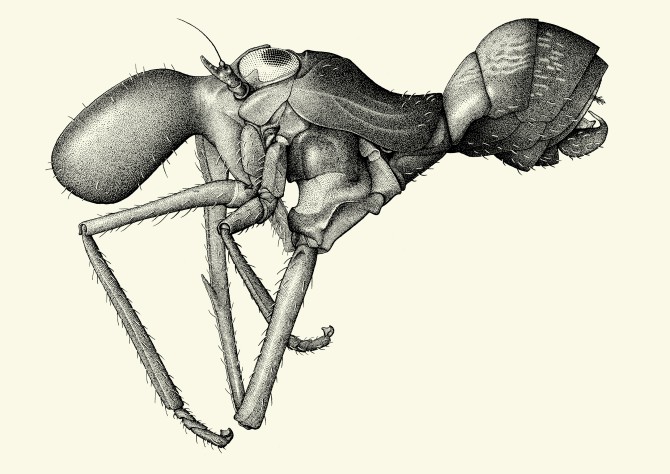

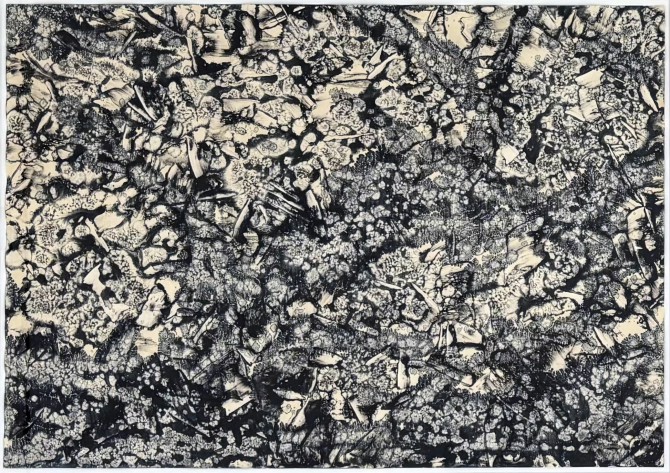

Oliver Thie, Formiscurra indicus, 2011, Ink on paper, 21 x 29,7 cm (SOLD)

Oliver Thie, Formiscurra indicus, 2011, Ink on paper, 21 x 29,7 cm (SOLD)

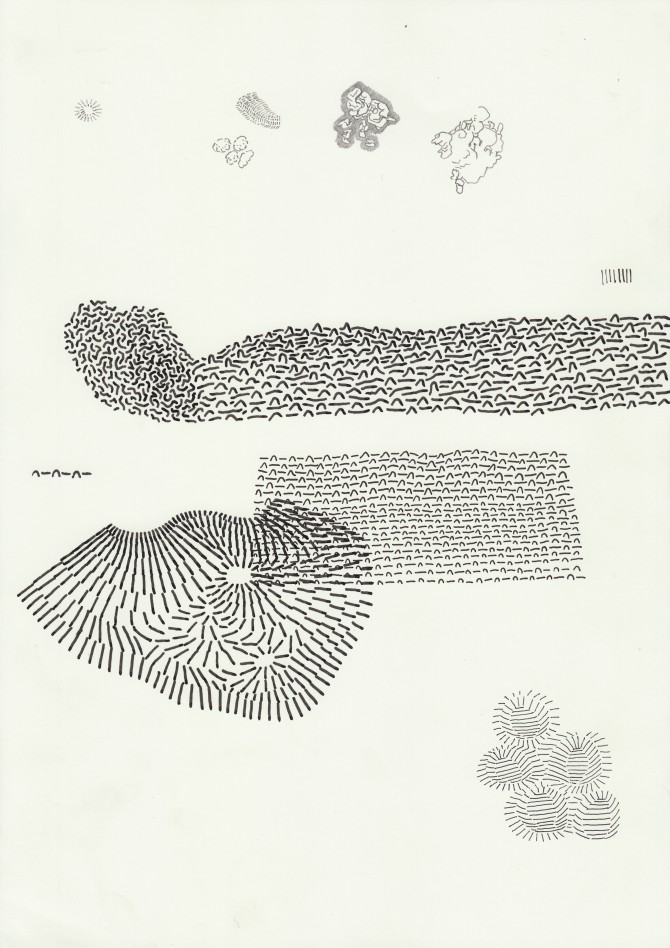

Oliver Thie, Untitled (Studien zu Oliarus polyphemus), 2015, ink and ink pens on paper, 29.7 x 21 cm

Oliver Thie, Untitled (Studien zu Oliarus polyphemus), 2015, ink and ink pens on paper, 29.7 x 21 cm

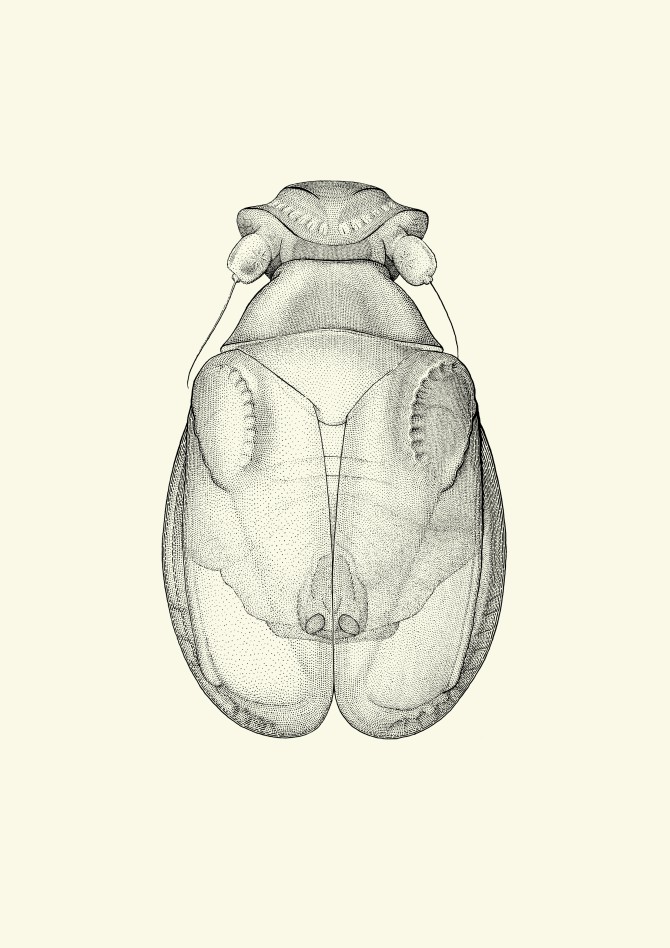

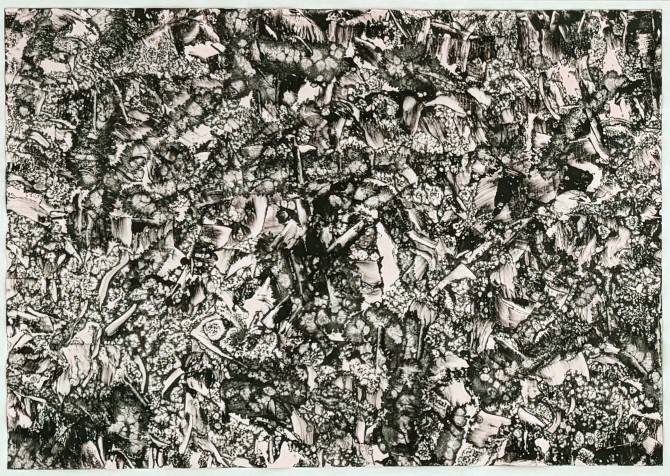

Oliver Thie, Meenoplus roddenberryi, 2012, ink on paper, 29.7 x 21 cm (SOLD)

Oliver Thie, Meenoplus roddenberryi, 2012, ink on paper, 29.7 x 21 cm (SOLD)

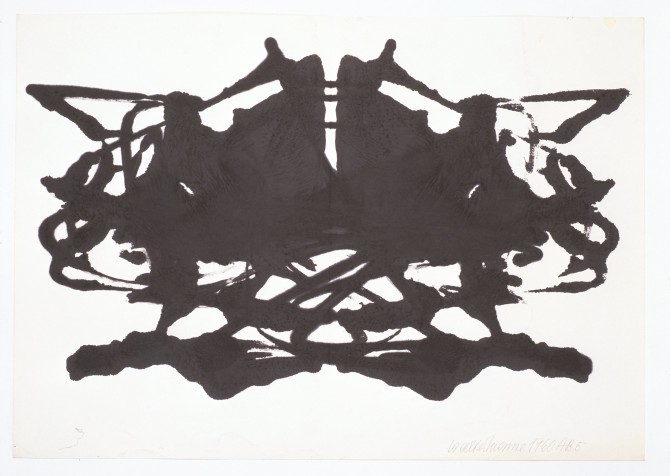

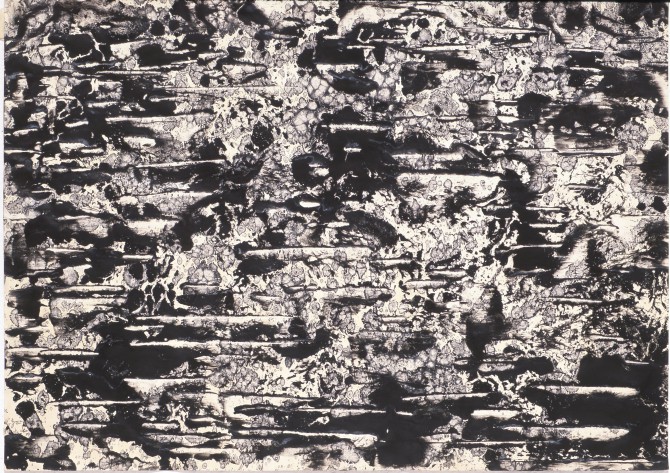

Walter Menne, Untitled (AB5), 1960, ink on paper, 60.7 x 85.7 cm

Walter Menne, Untitled (AB5), 1960, ink on paper, 60.7 x 85.7 cm

Exhibition view Georg Nothelfer Gallery. Photo: Katrin Rother

Exhibition view Georg Nothelfer Gallery. Photo: Katrin Rother

Britta Lumer, Gewitterwolke (dunkel), 2003/25, Ink on watercolour laid paper, 121,5 x 145,5 cm. Photo: Eric Tschernow

Britta Lumer, Gewitterwolke (dunkel), 2003/25, Ink on watercolour laid paper, 121,5 x 145,5 cm. Photo: Eric Tschernow

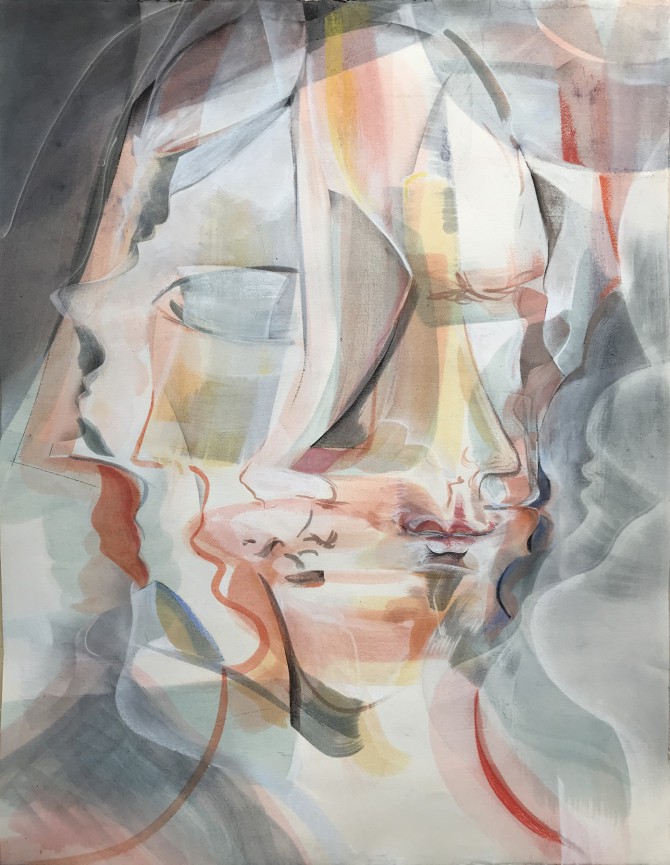

Britta Lumer, untitled (col ink), 2025, Sennelier ink and soft pastel on paper, 124 x 95 cm. Photo: Eric Tschernow

Britta Lumer, untitled (col ink), 2025, Sennelier ink and soft pastel on paper, 124 x 95 cm. Photo: Eric Tschernow

Britta Lumer, Nachtstadt hell, 2008, ink on paper, 56 x 76 cm, Foto: Eric Tschernow

Britta Lumer, Nachtstadt hell, 2008, ink on paper, 56 x 76 cm, Foto: Eric Tschernow

Exhibition view Georg Nothelfer Gallery. Photo: Katrin Rother

Exhibition view Georg Nothelfer Gallery. Photo: Katrin Rother

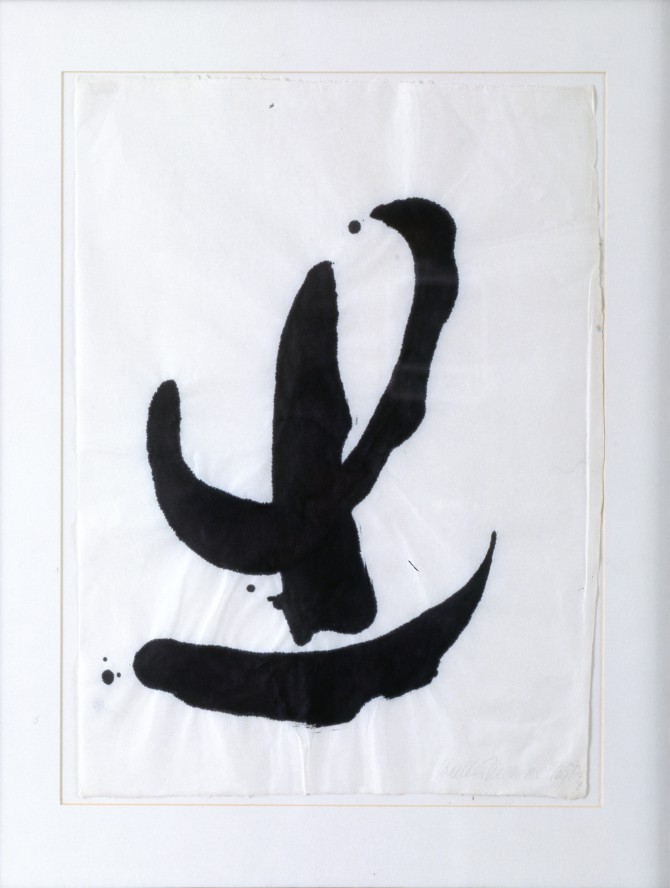

Walter Menne, untitled (P4g), 1965, ink on paper, 63.5 x 46.3 cm

Walter Menne, untitled (P4g), 1965, ink on paper, 63.5 x 46.3 cm

Andrey Klassen, Blaue Stunde, 2025, Ink on paper, 130 x 100 cm. Photo: Claus Sauter

Andrey Klassen, Blaue Stunde, 2025, Ink on paper, 130 x 100 cm. Photo: Claus Sauter

Walter Menne, Untitled, 1962-1, ink on paper, 42.2 x 59 cm

Walter Menne, Untitled, 1962-1, ink on paper, 42.2 x 59 cm

Walter Menne, Untitled, 1962-2, ink on paper, 42.2 x 59 cm

Walter Menne, Untitled, 1962-2, ink on paper, 42.2 x 59 cm

Walter Menne, Untitled, 1962, ink on paper, 42.2 x 59 cm

Walter Menne, Untitled, 1962, ink on paper, 42.2 x 59 cm

Exhibition view Georg Nothelfer Gallery. Photo: Katrin Rother

Exhibition view Georg Nothelfer Gallery. Photo: Katrin Rother

Andrey Klassen, Fabrik der magischen Schuhe, 2025, Ink and acryl on paper, 164 x 121,5 cm, photo: Claus Sauter (SOLD)

Andrey Klassen, Fabrik der magischen Schuhe, 2025, Ink and acryl on paper, 164 x 121,5 cm, photo: Claus Sauter (SOLD)

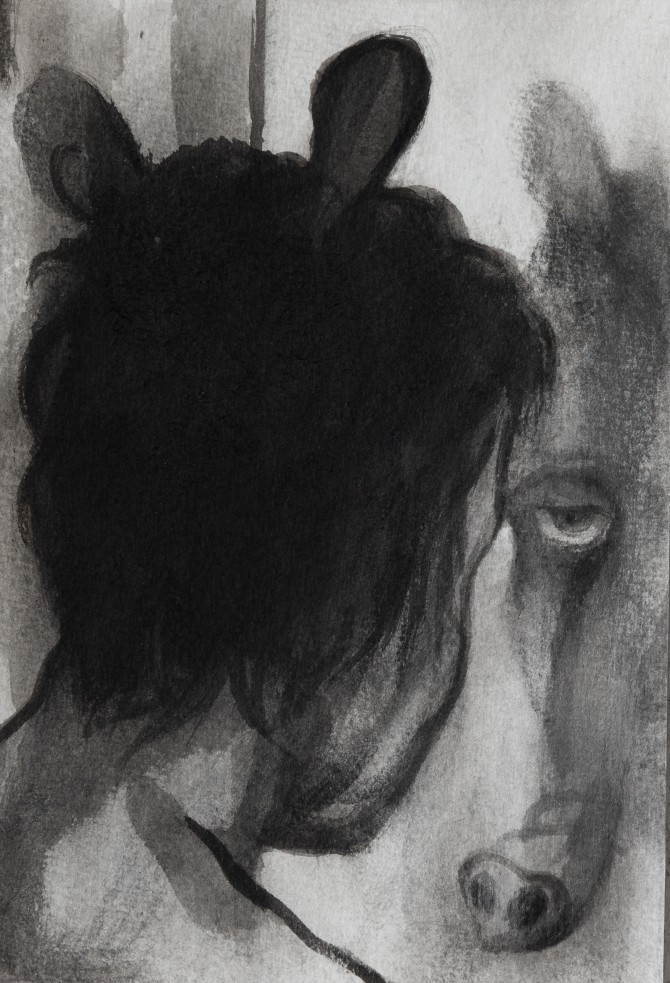

Andrey Klassen, Auf der Hut, 2025, Ink on Paper on Wood, 40 x 30 cm. Photo: Claus Sauter

Andrey Klassen, Auf der Hut, 2025, Ink on Paper on Wood, 40 x 30 cm. Photo: Claus Sauter

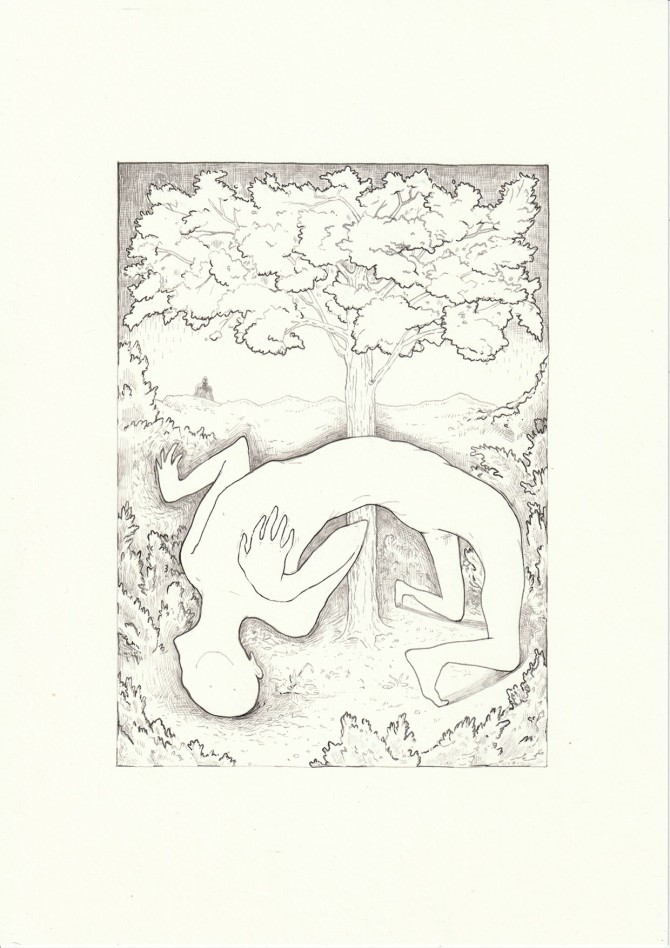

Andrey Klassen, Der Tag danach, 2024, ink on Paper, 23.5 x 16 cm. Photo: Claus Sauter

Andrey Klassen, Der Tag danach, 2024, ink on Paper, 23.5 x 16 cm. Photo: Claus Sauter

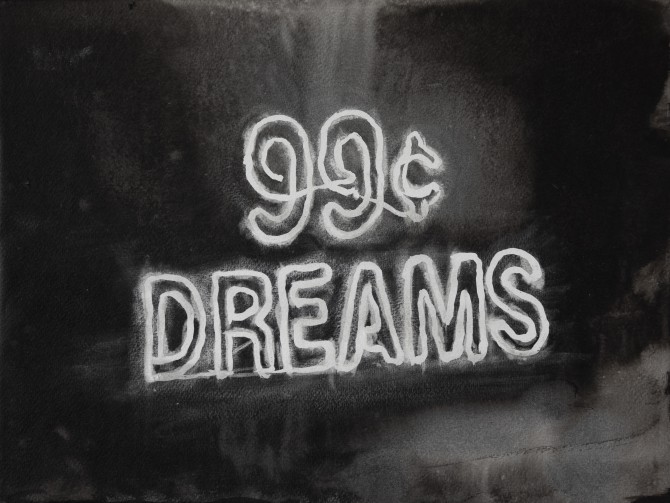

Andrey Klassen, Günstige Träume, 2025, ink on Paper on Wood, 30 x 40 cm, photo: Claus Sauter

Andrey Klassen, Günstige Träume, 2025, ink on Paper on Wood, 30 x 40 cm, photo: Claus Sauter

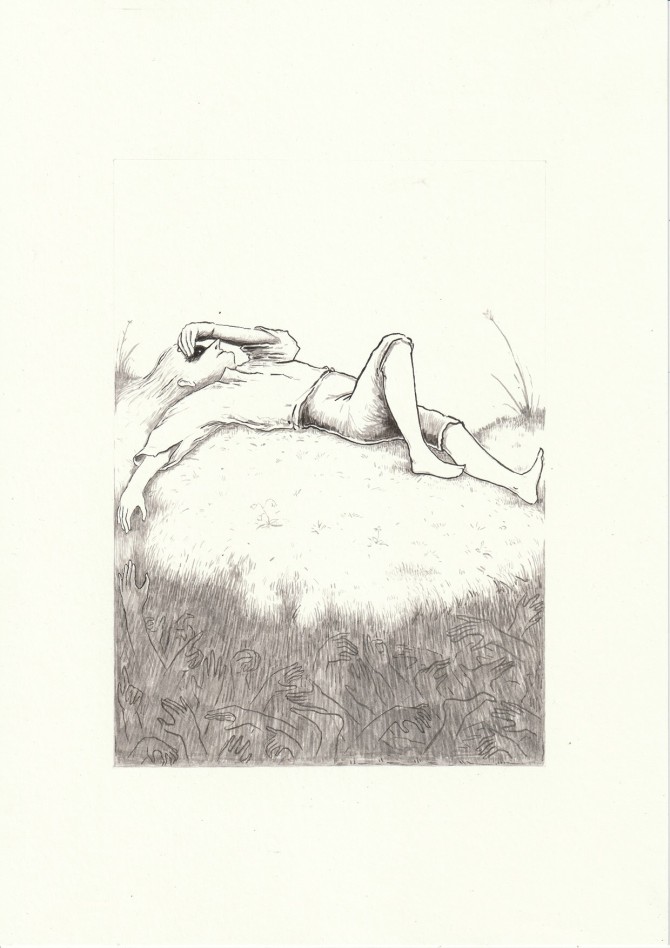

Andrey Klassen, Kindheitserinnerungen, 2025, ink on Paper, 25.8 x 18 cm, photo: Claus Sauter

Andrey Klassen, Kindheitserinnerungen, 2025, ink on Paper, 25.8 x 18 cm, photo: Claus Sauter

Exhibition view Georg Nothelfer Gallery. Photo: Katrin Rother

Exhibition view Georg Nothelfer Gallery. Photo: Katrin Rother

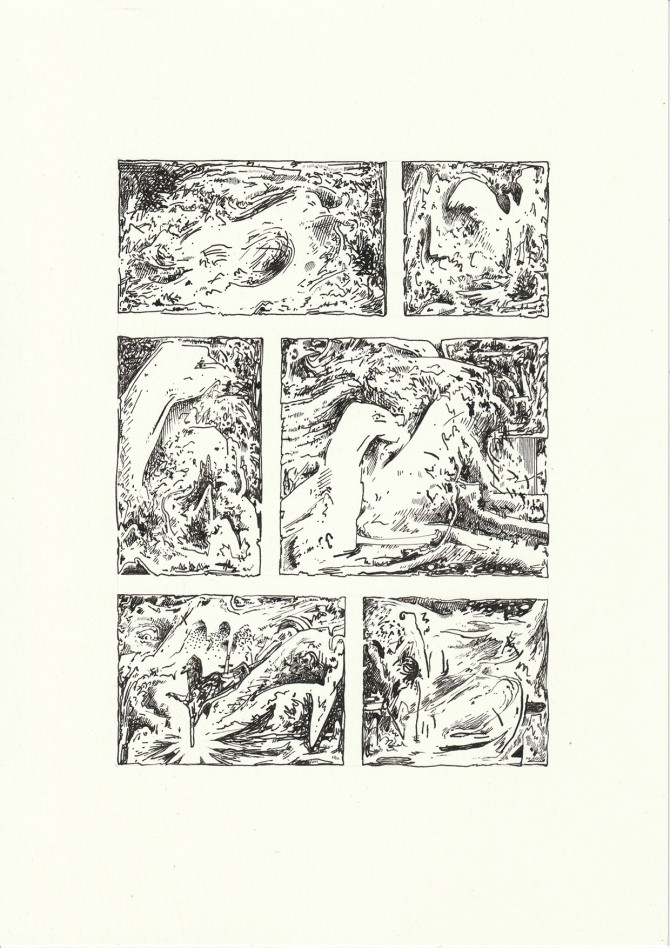

Toni Mauersberg, Was jeder erst mal tun würde, 2025, Ink on Resopal board, 120 x 60 cm

Toni Mauersberg, Was jeder erst mal tun würde, 2025, Ink on Resopal board, 120 x 60 cm

Mauersberg, Falsche Schatten, 2025, ink on paper, 29,7 x 21 cm

Mauersberg, Falsche Schatten, 2025, ink on paper, 29,7 x 21 cm

Toni Mauersberg, Krisis, 2025, ink on paper, 21 x 15 cm

Toni Mauersberg, Krisis, 2025, ink on paper, 21 x 15 cm

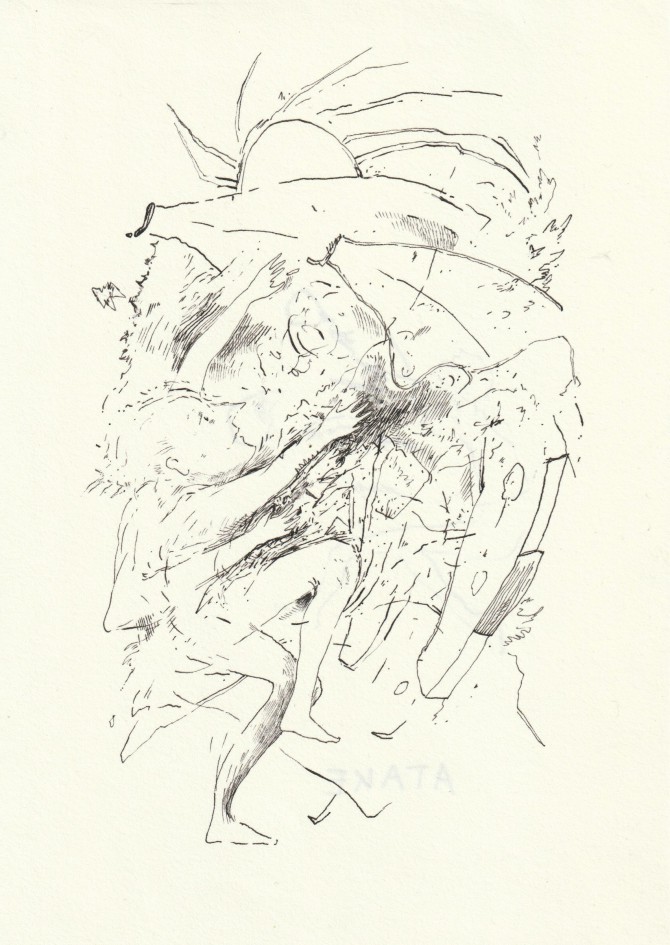

Mauersberg, Die heimliche Komödie, 2025, ink on paper, 29.7 x 21 cm

Mauersberg, Die heimliche Komödie, 2025, ink on paper, 29.7 x 21 cm

Toni Mauersberg, Drama 1, 2025, ink paper, 29.7 x 21 cm

Toni Mauersberg, Drama 1, 2025, ink paper, 29.7 x 21 cm

Exhibition view Georg Nothelfer Gallery. Photo: Katrin Rother

Exhibition view Georg Nothelfer Gallery. Photo: Katrin Rother

Stöhrer, Untitled, 1966, mixed media on paper, 54 x 70 cm, P66.39

Stöhrer, Untitled, 1966, mixed media on paper, 54 x 70 cm, P66.39

Walter Stöhrer, Untitled, 1977, Mixed media/ink/paper, 30.4 x 43 cm. Photo: Katrin Rother

Walter Stöhrer, Untitled, 1977, Mixed media/ink/paper, 30.4 x 43 cm. Photo: Katrin Rother

Walter Stöhrer, Untitled, 1956, ink on paper, 37.5 x 29.5. Photo: Katrin Rother

Walter Stöhrer, Untitled, 1956, ink on paper, 37.5 x 29.5. Photo: Katrin Rother

Henri Michaux, Untitled, 1962, mixed media on arches vellum, 74.8 x 106.1 cm. Photo: Katrin Rother

Henri Michaux, Untitled, 1962, mixed media on arches vellum, 74.8 x 106.1 cm. Photo: Katrin Rother

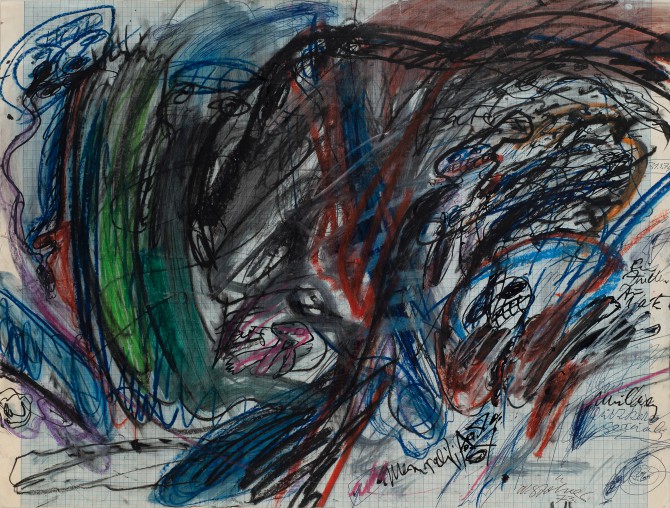

Walter Stöhrer, Untitled, 1973, mixed media on graphic paper, 56 x 74 cm

Walter Stöhrer, Untitled, 1973, mixed media on graphic paper, 56 x 74 cm

Opening: April 30, 6 - 9 pm

Special opening hours during Berlin Gallery Weekend: May 2 - 4

Fri 12 – 9 pm

Sat 11 am – 6 pm

Sun 11 am - 6 pm

Artist talk: May 3 at 2 pm

Galerie Nothelfer is delighted to be showing seven different positions on the subject of ink drawings. Both historical positions from the post-war period and contemporary artists will offer an insight into the medium.

Galerie Nothelfer is delighted to be showing seven different positions on the subject of ink drawings. Both historical positions from the post-war period and contemporary artists will offer an insight into the medium.

When - as in the INK exhibition - the material becomes the curatorial bracket, there is a justified expectation that this material itself has something special to tell, that it can become the carrier of discourses that unite both historical and processual aspects, without this necessarily leading to an antagonistic clash of form, material and content.

INK, whereby there is often a conceptual blurring in the German translation between ink and China ink, thus becomes the theme of this exhibition of works on paper and other pictorial media, which spans a period of 60 years and thus connects the informal basis of the gallery programme with current positions.

In art history, ink is the generic term for all colouring liquids used for writing and drawing. It is created by mixing water, sooty particles and binding materials. There is also the real cuttlefish sepia and iron-gallus inks from chemical reactions. In fact, even among specialists, there is a terminological confusion due to the large number of liquids that contain colour pigments.

However, ink as a material has a long art-historical tradition in both the Orient and the Occident, and its proximity to the act of writing in particular opens up a wide range of relational contexts. Put simply, in calligraphy, writing becomes an image and in this position of the semantic in-between - between pictogram and ideogram - ink plays a decisive role. Its flow determines the ductus of the form. Either the control succeeds or it fails. Whether pen or brush. A tool held by the artist - and there are countless of them - manipulates the liquid and determines its form, its expansion and its intensity.

Ink is first and foremost something that flows. ‘Panta rei’, one might say, its liquidity is its core characteristic. Depending on the concentration, it is either washed, i.e. diluted with water, and appears in translucent swathes, or it appears in the deepest darkness, so saturated that it infiltrates the material like a concentrated brew. Controlling or even stopping its flow becomes a challenge. The picture carrier acts as a necessary collaborator. It absorbs the puddles and streams until every pore is filled.

Seen in this way, ink is often an agent of the diffuse. This visual state of aggregation can, of course, be due to a deliberate coincidence, allow for a materially implicit aleatoricism and also provoke it.

Britta Lumer's inked cloud paintings, city silhouettes and heads play with the fluidity of (not only) natural phenomena and the impossibility of capturing the immaterial. The 19th century produced a theory of clouds, a morphology and typology, only to realise that they cannot be dealt with on the scientific level of form alone. Equally fleeting are the forces of movement of the mimic in a face, which make a real fixation of a single expression seem impossible. In the dissolution of form, the mimetic material fades and diffuses into an ambiguous sign. This is what happened in the blot of the British landscape artist Alexander Cozens in the 18th century, whose accidental practices were intended to set the forces of composition in motion, in the experimental blot drawings of the writer Viktor Hugo or in the Rohrschacht test of the early 20th century. The blot is a perpetual motor of creative work.

In Andrey Klassen's densely constructed theatrical works, shadows made of ink dance in rooms in various degrees of darkness. Threads are spun that traverse the space. Klassen draws lines with ink that have sharp edges and crystallise like a pictorial antidote to the soft, fluid caressing of the forms.

Walter Menne, who was both a pathologist and an artist, operates at the edge of the written word. The word calligraphy is always to be avoided at all costs, rhythm and intuition, a musical trace beyond notation. His blots and drippings are reminiscent of microscopic pictures, as well as the Americans Jackson Pollock or Franz Kline, without these being direct role models. There are clear settings and explosions, automatic writing and condensations and always a balancing of white ground and black sign.

In Toni Mauersberg's small-format ink works, two elements occasionally face each other or are layered on top of each other. In this way, figure and ground come together in an expanded pictorial space, while the different gestures, both abstract and figurative, are arranged and confronted with each other. In the current exhibition, she also transfers this vocabulary to large-format Resopal panels, whereby the physical gesture necessarily changes. What was compressed - the wiped and scratched traces - expands into the space.

And in Walter Stöhrer's gestural swings and text fragments we find various forms of dynamisation of the surface, linguistic signs without semantic order, ciphers, formal abbreviations are thrown onto the sheet in rapid succession. The ink (black and coloured) flows and splashes even more quickly than the oil paint, it is sometimes so fast that it overtakes the artist's controlling gaze, rushing ahead without obedience.

‘Shadows of shadows, ashes of wings’, reads a poem by Henri Michaux, who captures the ephemeral on paper. A fleeting flare-up from the depths of consciousness, often known to be under the influence of hallucinogenic drugs such as mescaline. His écriture without text creates dense rhythmic fields of signs alternating between ink and paper. A movement is created that obscures precisely this relationship: ground and figure. The ink becomes an actor in this movement.

Oliver Thie has also been inspired by the shadows of objects in the past. For example, how they reveal something characteristic of a stone that would otherwise remain invisible. In the works presented here, on the other hand, visualisation is an enormously precise task. And in this greatest possible contrast to the free gestural or atmospherically evocative use of ink, as a precise chronicler of the factual, he also stands in a line of tradition of artistic-scientific draughtsmen. Thie injects the ink into the skin of the paper with the needle-sized tip of a drawing instrument, similar to a tattoo artist. All gesture has disappeared, and we stare as if through a magnifying glass at the monstrous creature that confronts us. In the 17th century, it was the British scholar Robert Hooke who produced microscopic precision drawings of fleas and tiny creatures before the arrival of photography. They showed that the drawing was both an instrument of depiction and an instrument of knowledge. Ink has also left its mark in these fields.

Text: Jan-Philipp Frühsorge